Name: Nigel Horwood

Year of Birth 1956

Lives: Surrey, UK

Type of IBD: Crohn's disease

Diagnosis Date: July 1978

Symptoms at Diagnosis: Urgent diarrhoea, weakness, cold to touch, weight loss

Details of Surgery: Repair to perforated bowel; Removal of 14cm of terminal ileum and ileocaecal valve and temporary ileostomy with reversal (Ileocaecal resection)

In Spring 1977 I turned 21 and had reached the halfway point of my college degree. During the summer I worked in a local factory and by the time I returned to college was feeling very fit. Then something changed. I found myself having to dash off to the bathroom frequently.

Eventually I plucked up courage and, in October, sought medical advice. It was the thought of discussing bodily functions with a stranger that made me hesitate. The first attempt at treatment was Imodium but that didn’t work. By now I was feeling very weak and always cold to the touch.

It was decided I needed to have a “procedure”, my first ever, and a lovely one with which to “break my duck” - a barium enema. X-rays were taken and when the diagnosis came through it was “spastic colon”, nowadays called irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). The doctor put this down to “nerves” and prescribed a drug called Nacton. It didn’t work, which is hardly surprising as it was used to treat peptic ulcers. I should have questioned the doctor’s judgement but in those days doctors were gods and you treated them as such.

Over the course of a year my weight dropped from 73 to 54kg. I went to see the doctor again and luckily he was on holiday. I saw a locum who was shocked at my condition and arranged for me to see a consultant the following day. He was similarly shocked and said I needed to be in hospital. Two days later I was sitting in Croydon’s Mayday Hospital, ostensibly for tests, but I think it was also a chance to give my system a complete rest. It was July 1978.

After three days I was told I had Crohn’s disease. It meant nothing to me but the consultant explained they didn’t know what caused it and there was no cure. I would have to live with it from now on. They were in no hurry to discharge me whilst I slowly regained some strength, helped by four units of blood. I was started on a combination of salazopyrine and codeine phosphate.

Again the drugs didn’t work and in September I started my long-term relationship with Prednisolone, at 30mg/day. It worked! I completed my finals and started my first real job. Things were looking up.

First surgery

Fast forward to June 1979. One morning I started getting a terrible lower abdominal pain. It was so bad, I thought ‘it must pass’ - but it didn’t. An ambulance was called and rushed me to Croydon General Hospital with suspected appendicitis. The surgeon prepared to do an appendectomy but once he had made the first incision found a perforated gut which had leaked into the abdominal cavity. What should have been a simple, routine operation had suddenly escalated to another level.

The surgeon’s notes made depressing reading. My intestines were in a very bad way. There was even a mention of finding two strictures near my terminal ileum. The decision was taken to repair my bowel, clean out the cavity and sew me back up. The appendix was left in position as they didn't want to risk septicaemia. I never found out why the strictures were left in-situ.

Once back on the ward I spent most of the next three weeks being fed intravenously. I returned home for further recuperation. By mid-August I was well enough to go back to work and was now managing on 15mg/day of steroids.

The quiet years

Then followed a relatively quiet period of nearly 20 years! I had a few flare-ups but never severe enough to end up in hospital. I kept trying to reduce the steroids to 5mg/day but could never get below 7.5mg/day without having problems.

At the end of 1997 I started complaining of abdominal pain. A colonoscopy showed an ulcerated stricture in my terminal ileum. There was talk of doing a balloon dilation but it was decided to wait and see if it worsened. For the first time the consultant mentioned giving me azathioprine instead of steroids. The problem was the frequency of blood tests required, something I simply couldn’t fit in with work. I continued with the steroids but jumped to 50mg/day.

In May 1999 the abdominal pain became dramatically worse. The steroids were increased to 60mg/day, the highest I had ever been on, whilst I waited for a barium follow through. It showed that the stricture had further narrowed with the small intestine down to the size of my small finger. My consultant gave me a stark choice - start taking azathioprine (the “last resort”) or have surgery. I didn’t fancy another stay in hospital so chose the drugs.

After a few teething problems - flu-like symptoms, aching joints - the azathioprine worked well and life returned to normal. I was holding down various stressful jobs, which included trips to locations such as Algeria and Kazakhstan. My hobby was also fairly full-on - competing at carriage driving.

In 2000 we moved house and my care moved to East Surrey Hospital, just 10 minutes away. I returned to equilibrium for another eight years.

Interesting times

In May 2008 a routine blood test showed my platelet count was dropping. We weren’t too concerned at first but more tests showed that the level was now below 100. I was diagnosed with thrombocytopenia, azathioprine being the most likely culprit. It was stopped. Given that this was the “last resort” before surgery I prepared myself for the inevitable. My consultant said that I should self-medicate with steroids as required.

Another year passed and back pain started to keep me awake at night. A CT scan was ordered. When the radiologist’s report came through it said “complicated ileal disease with suspicion of fistulas”. It looked like it would be surgery but was surprised to be told that there was a “final last resort” - infliximab. The problem was the cost and getting Primary Care Trust approval. The request was sent. After a week I had heard nothing so decided to take matters into my own hands. I managed to find out who I needed to contact, rang them and within an hour had the necessary signature.

After the first two infusions my consultant wrote “he is a changed man”, but after the third one I relapsed. I was told to prepare for surgery, at East Surrey Hospital, within four weeks. My wife came along to a meeting with my consultant, his boss and their surgeon, to discuss the surgery and timing. When we arrived they had some surprising news. Having reviewed the CT scan they did not believe the hospital had the necessary facilities to handle my recovery. They were referring me to St.Thomas’ in Westminster. A bit of a shock.

Off to London

I went up to meet the surgeon and get accepted onto his list. We immediately hit it off. He was very matter-of-fact about the whole process and it helped put me at my ease. Having been given the operation date, October 11, 2010, he wanted to carry out a flexi sigmoidoscopy as he was concerned that my small bowel was fistulating into my colon. He warned me that I might need a stoma depending on what he found. Two weeks later he scoped me and was pleased to see that the colon was “just an innocent bystander”.

St.Thomas’ runs an Enhanced Recovery Programme which aims to reduce recovery times for patients undergoing colorectal surgery. You can choose to be treated under that regime or go the conventional route. For me it seemed a no-brainer. The next meeting was with the Enhanced Recovery Nurse (ERN). She spent two hours with my wife and I going through all aspects of the pre and post-operative care. She took us into the ward, on the 11th floor, where I was expected to stay. The view across London and the River Thames was stunning.

I had a further three visits to the hospital before admission. Two for pre-operative assessments, making sure that I was fit enough for surgery, and the third with the stoma nurse to mark the best position for the stoma, should I need one. I came away with a large, black cross on my abdomen.

I started writing a blog recording the lead-up to the surgery, in the hope that it might enlighten other inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) patients about to follow a similar path.

Surgery

I arrived at St.Thomas’ the evening before the operation and was put in a private room but told not to get used to it. It was strictly one night only. I sat eating my final meal watching the sun setting over the Houses of Parliament. I had become very relaxed about the whole process and managed to get some sleep. Early the next morning one of the surgeons came to introduce himself. I would be last on that day’s list. Then the anaesthetist appeared to run through the risks of using an epidural and to ask me to sign consent forms for the operation. He expected that I would go down to theatre about 11:30am.

That start time slipped by an hour and I was finally taken down to theatre at 12:30pm. Within a few minutes of arriving in theatre I was drifting off into oblivion as the anaesthetic took over. I was hoping that the large black cross on my abdomen was still intact when I woke up. The operation, which lasted about four-and-a-half hours, was later described by the surgeon as “complex and enjoyable”.

Recovery

I woke up in recovery violently shivering. One of the surgeons came over to see me and lifted the blanket. The black cross had gone and was replaced by a stoma. Another new experience to deal with. The medical team were concerned about my temperature, wrapped me in a bair hugger blanket and gave me a warm drink. At around 8pm I was allowed up to the ward. I felt great on a drug-induced high.

It was planned I would be in hospital for a week after the operation - but it worked out closer to two. My digestive system went into lockdown (post-operative ileus) for several days which delayed my discharge. It did however give me more time to learn how to cope with a stoma.

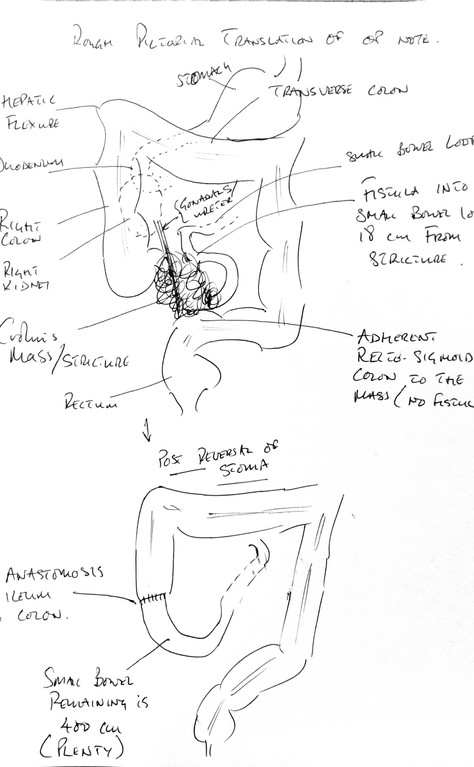

The discharge note spelt out, in technical terms, what the operation involved: “He underwent laparotomy, ileocaecal excision of locally perforated Crohn's mass/stricture and excision of enter-enteric fistula. There was gross right para-colic and midline fibrosis with terminal ileum drawn into a chronic abscess/fibrosis. An inflammatory mass was fistulating into a more proximal ileal loop, closely adherent to the recto-sigmoid colon. A double barrelled ileo-colostomy was formed in the right iliac fossa.” No, I didn’t understand it!

In layman’s terms they removed 14cm of my terminal ileum and ileo-caecal valve and formed a temporary ileostomy. The difficult bit was separating the Crohn’s mass from the surrounding tissues and muscles, including my back muscles.

Living with and without a stoma

I quickly got into the routine of changing pouches. My confidence grew rapidly. There were a couple of problems along the way. One saw me end up in A&E with my pouch filling with blood. It turned out to be an abscess which had burst and not the internal bleeding that I had feared. A couple of weeks later the stoma started to prolapse, which was brought under control with an elasticated support belt. Life continued and I returned to work.

After Christmas I saw the surgeon’s registrar and agreed a date for the reversal operation - early April. There was one proviso, the haematologist at East Surrey had to agree for the operation to proceed given my low platelet count. Try as I might it was impossible to see the haematologist quickly enough and once I had seen him I needed his written consent to proceed. The planned surgery was getting ever closer and my frustration was rising. Eventually the ERN at St.Thomas’ rang to say that the operation was being cancelled. You can imagine my feelings.

I kept pressing to get the consent letter and it finally arrived two days after the original operation was due. I rang the ERN to ask for a new date but was told it was down to the surgeon. Time for some more direct intervention. I emailed him with a copy of the haematologist’s letter. A couple of days later the call came through - 13th June, later than I had hoped for but at least I was in his diary.

I knew what to expect this time. The operation was fairly simple and only took around an hour. I was back in recovery by early afternoon. There was then a long wait to have a platelet infusion. Once back on the ward I was given supper. Would my system go into lockdown again? Yes it did. The nausea was worse than before, bad enough to have an NG tube for a whole weekend. Discharge was delayed and I ended up spending 11 days in hospital.

During my stay I was asked if I would like to move my outpatient care to St.Thomas’. Given their facilities and resources I jumped at the chance and have never regretted it.

After the reversal I took no Crohn’s disease medication apart from loperamide . I was expecting my digestive system to return to normal. I had been told that I would need to take additional vitamins and have B12 injections as the section of bowel removed usually absorbed them as well as salts. I didn’t understand the significance of that final word and that it referred to the bile acid in the digestive process. Many times I would find myself with an “upset stomach” and wondering if I had eaten something dodgy, picked up a virus or the dreaded Crohn’s disease was flaring.

It wasn’t until Autumn 2014, when I was sent for a SeHCAT test, that the result came back - “severe bile acid malabsorption”. Suddenly it all fell into place. I was prescribed a bile acid sequestrant, Colesevelam, and in combination with loperamide it stabilised my digestive system.

Bringing the story up to date

In late 2016 I had a routine calprotectin test which returned a value of over 500 and by the next time it had risen to 900. Meanwhile I was feeling completely asymptomatic. My consultant could not understand this increase. He carried out a colonoscopy to see if the inflammation had returned but saw nothing untoward. He was so concerned that something might have been missed that he asked his colleague to repeat the procedure. Still no sign of any inflammation. It appeared that remission continued despite the calprotectin results.

The mystery was finally solved after a VCE (Video Capsule Endoscopy) showed inflammation in my small bowel and explained why the calprotectin had, by then, reached 1900. The decision was made to start treatment with a monoclonal antibody. Vedolizumab was chosen for a number of reasons and I had my first infusion in May 2019. It is known to take a while to become effective but after just two infusions my calprotectin had dropped by 75%. This was looking hopeful until it plateaued and stubbornly sat around the high 400s. I was starting to think it might not be working.

Then, after the 9th infusion, there was a dramatic drop to under 50, the threshold for “normal”. Just before Christmas 2022 I had my 25th infusion and the calprotectin was just 34. A good way to start the new year.

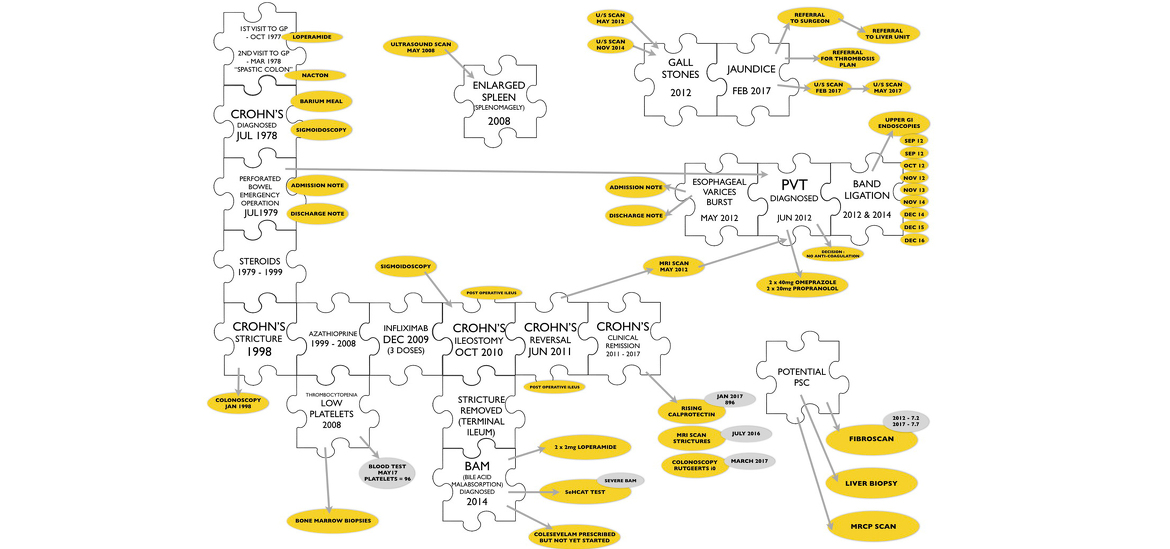

Piecing it all together

There were still unanswered questions about my IBD history and links between other conditions that had arisen along the way. Would any of my medical records be available to do a little detective work? Surprisingly they were and went all the way back to October 1977. I decided to use a combination of my old blog posts and medical records to write a narrative that might answer some of my questions and prove of interest to other IBD patients. It took a while but I have finished turning my narrative into a book “Crohn’s Disease - Wrestling the Octopus” which is available as a free download in eBook, Kindle and pdf formats from www.wrestlingtheoctopus.com. I hope you find it interesting, living with Crohn’s disease certainly has been!